Three years, that’s how long it took me to do this!

THREE YEARS!!

I’d had indigo crystals for a third of decade and only got round to using them a week ago.

What took me so long and why now?

Cooking up chemicals with two small children and an inquisitive dog around scared me a little and I never seemed to find an opportunity to set it up.

But last weekend, disappointed I couldn’t go to the Amsterdam Denim Days festival to try the indigo dyeing workshops, I dug out my dyeing kit and had an indigo party in my garden! Not quite as cool as a weekend in Amsterdam, but hey, we can’t have it all.

After two weekends of dyeing experimenting, here’s what I’ve learned so far.

Tip One: Be Prepared

Gather everything you’ll need before you begin and make sure pets and children are out-of-the-way.

Obvious points, but you don’t want to be in the middle of cooking up your dye vat and realise you forgot something important like the thermometer – ahem like I did!

What you’ll need:

1) The indigo dyeing chemicals.

Indigo dyeing kits vary and many online suppliers offer them. Follow the guidelines and instructions of the supplier of the kit that you’re using, it may differ from the kit I used.

My kit consisted of indigo crystals, spectralite and soda ash bought from Wild Colours online shop. Some kits have the chemicals pre-combined but I bought mine individually and had to concoct the dye vat mixture myself.

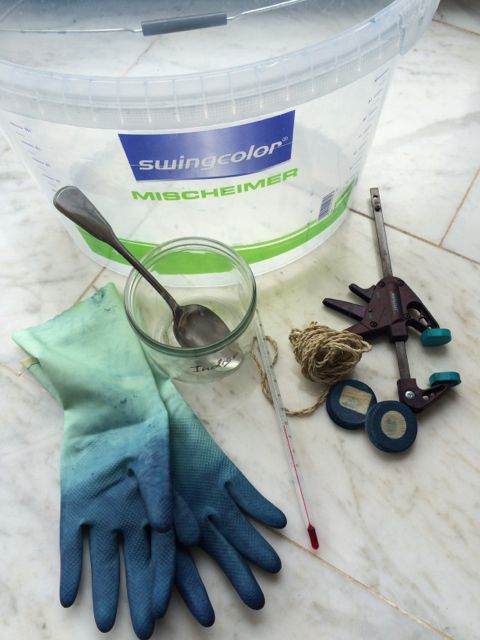

2) Equipment and shibori-making materials.

– 2 Buckets or similar containers – one 10 litre. I used one bucket filled with water to pre-soak my fabric in and another to transfer the dyed fabric from the dye vat to the washing line to hang.

– measuring jug to measure the water needed to mix up the chemicals.

– spoon for mixing the chemical/water solution.

– protective gloves otherwise your hands’ll be like the rubber gloves in the pic above.

– measuring scales to weigh the chemicals.

– 2 glass jars to put the chemicals in.

– thermometer to check the dye vat temperature.

– string and/or clamps and wooden shapes, scissors for shibori resist dyeing to make the patterned pieces. I got the clamps and wooden pieces from my local DIY store.

– stainless steel pan suitable for heating to make the dye vat in. Mine has a lid and is 10 litres – the volume needed to dye one kilo of fabric. Make sure you use a pan that you don’t use for cooking because you won’t be able to use it for cooking food again.

– portable cooker such as a camping stove to heat up the pan of water, if you’re cooking up your dye vat outside like I did.

– face masks. I used this the first time but didn’t bother the second because being outside, the fumes didn’t seem strong but it’s recommended to use face protectors.

– apron or old clothes – any splashes are going to stain whatever you’re wearing blue.

– white vinegar for adding to the rinsing water after the fabric’s been dyed.

– Washing line outside to hang the fabric so that the oxidisation process can occur (when it turns blue). I set up a temporary line using some climbing rope I had.

3) Fabric

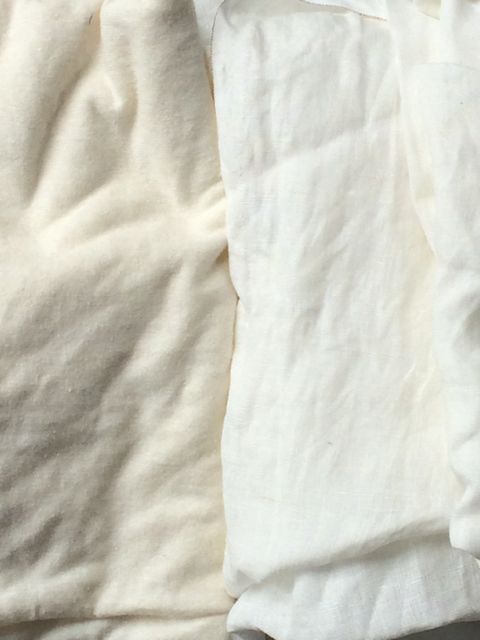

I used organic natural coloured hemp jersey, off white coloured linen/cotton, a heavy duty untreated cotton jersey and organic cotton twill in for-dyeing quality. You could use anything including garments already made but it’s advisable to pre-wash fabrics and garments before dyeing.

Tip 2: Give yourself plenty of time

One mistake I made first time was not allowing enough time. We spent so long preparing, by the time we started to heat up the pan of water and mix the chemicals it was already getting late in the evening and the kids were hungry, etc, etc. Not an ideal start!

The preparation, such as gathering all the things we needed and folding and clamping the fabric for the shibori experimenting took much longer than we anticipated. You then need to heat the water in the pan to 50 degrees celcius, mix the chemicals, add these to the heated water in the pan and then add the fabric. The fabric remains in the vat for about five minutes and then is hung for 15 minutes, rinsed and then this process is repeated if you want a darker colour.

The fabric then needs to be rinsed and hung outside overnight. Depending on how many times you put each fabric in the vat and how many items you’re dyeing, this process adds up to a fair chunk of time, which ideally you don’t want to rush.

Rushing isn’t good because it can mess up the indigo oxidisation process which is what makes the fabric turn blue. When you put the fabric into the dye vat, the indigo dyeing mixture is green/yellow and it’s only when the fabric emerges from the vat, hits the air and oxidises, that it changes colour to blue. For this reason, you have to lower your fabric into the vat slowly and remove it carefully and slowly to avoid introducing air into the vat which’d oxidise the indigo crystals prematurely before they’ve had a chance to bind the colour to the fabric.

I’d also suggest keeping a time slot open the following day post dyeing for the rinsing and washing of the dyed fabrics. This process is time consuming so don’t underestimate this.

Tip 3: Dye Outside

If possible I’d recommend dyeing outside. Dyeing in the garden was perfect because we were able to immediately hang the fabrics on a line to drip while they oxidised when we removed them from the dye vat. It saves a lot of mess indoors and is well-ventilated for the chemical fumes.

We kept our dye vat for a week sealed with the lid on the pan after dyeing but it had already oxidised by the second dyeing session and could no longer dye the fabric, so we disposed of it down an outside drain and rinsed the drain with water.

Conclusion

Indigo dyeing is lots of fun and produces beautifully imperfect results. We didn’t know how each piece of fabric’d turn out until the end of the dyeing process, which made each hand-dyed piece unique and kept the dyeing process exciting.

Different fabric types reacted differently to the indigo dye. The way the fabrics were pre-treated before they were dyed also affected the results. For instance I ironed the fabrics before I dipped them into the dye vat in the first dyeing session and put them in the vat twice. For the second dyeing session, I didn’t pre-iron and only put the fabrics in the dye vat once. The second batch is much patchier and less saturated than the first ironed batch and a lighter shade of blue. I like the results from both sessions though so I definitely recommend experimenting.

Have you tried indigo dyeing? What tips would you offer someone indigo dyeing for the first time? Please let me know in the comments below.

If you enjoyed this blogpost and would like to keep updated, sign up for the YoSaMi newsletter by leaving your email address in the box at the top of the sidebar.

Have a great week and happy dyeing,

Christine